The Pinal County Board of Supervisors rejected the proposed Valley Farms Energy Center in a split 2-3 vote during their April 30 meeting. A supermajority vote was required because at least 20% of property owners, by both area and number, within 300 feet of the project site filed formal objections, triggering the condition under A.R.S. § 11-814, which mandates a supermajority in such cases and was noted during the presentation. Supervisors Mike Goodman and Stephen Miller voted in favor, while Supervisors Rich Vitiello, Jeff McClure, and Jeff Serdy opposed the project, which had previously been recommended for denial by the Planning and Zoning Commission.

The Vote and Supervisor Positions

Supervisor Goodman emphasized the growing energy demands in the county, noting that the vast majority of San Tan Valley and Maricopa residents leave Pinal County for work. He highlighted the board’s strategic initiative to bring employment centers to the area, which requires sufficient power infrastructure and energy. Goodman noted that whenever companies look at coming to the area, “they’ve looked at two factors, water and energy.” He cited a two-day power outage in Gilbert last summer as an example of why energy reliability is essential.

Chairman Miller cited property rights, stating, “I look at it with the property rights. I’m a property rights-type person.” He added, “This is not harming anybody in the surrounding area. The lands adjacent to this are farms, and they’ll be able to continue to farm.” He also noted the county’s need to generate more tax revenue, explaining that while solar projects depreciate over time, after 10 years “it flattens out. It’s there. So it’s more than what we would get on farmland.”

Supervisor Vitiello questioned project benefits for local residents. When Kendall Riley, the county planner, noted that “applicant has estimated that around 70 letters of support have been received,” Vitiello responded, “I probably read at least 30, 40 of ’em, if not 50 of ’em, that were not from the area.” Vitiello also counted that during the meeting, thirteen or fourteen people spoke, with three from Coolidge in favor and approximately nine from Coolidge against the project.

Supervisor Serdy conveyed that all the mayors in the eastern region of Pinal County that he communicates with opposed the project, stating they “don’t think they can grow into this, up against this.” He added, “Once you get this, you’re not gonna get anything else.”

Project Overview and History

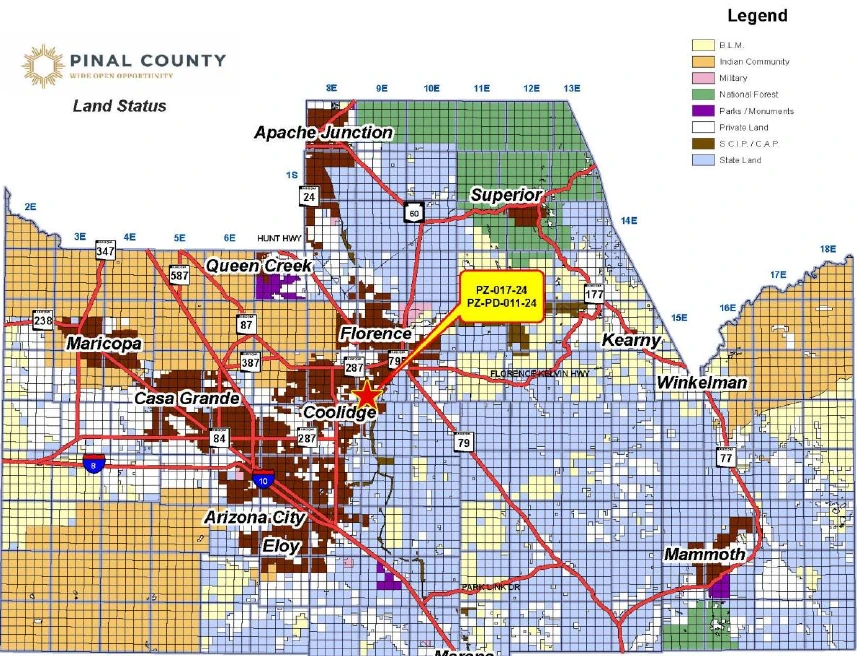

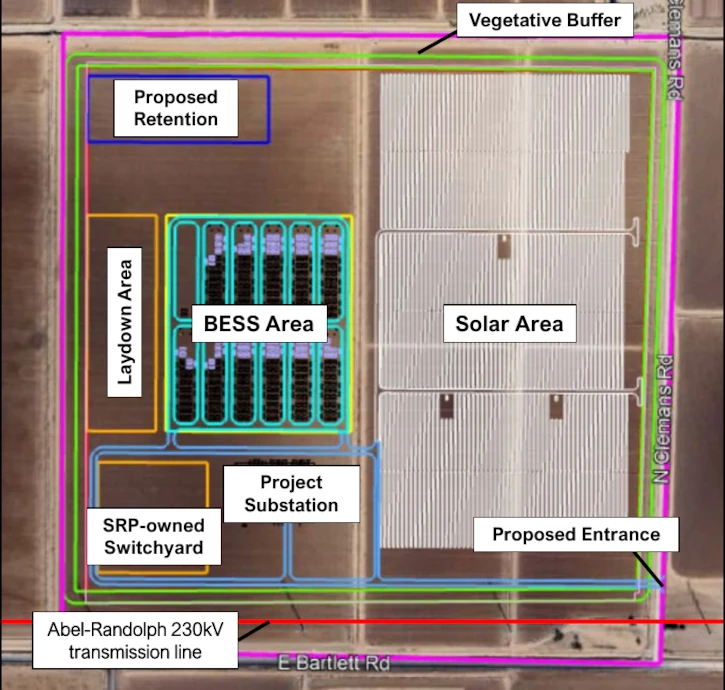

The Valley Farms Energy Center proposal aimed to rezone 160 acres from General Rural to Industrial (I-3) zoning with a Planned Area Development overlay. The project, located at the northwest corner of East Bartlett Road and North Clemens Road in the Coolidge/Valley Farms area east of Highway 87, would house a 10-megawatt photovoltaic solar facility with battery energy storage.

Kendall Riley, a county planner, explained that the project included solar panels, electric collection systems, site substation, and battery energy storage. The site plan positioned solar arrays on the east side of the property with transmission lines and battery storage on the west side, including a 100-foot setback around the property perimeter.

This proposal marked the latest step in a process that began in 2022. Ralph Pew, representing NextEra Energy Resources and the Wuertz family, noted that the Board of Supervisors had approved a comprehensive plan amendment in January 2023 designating the land for green energy production. The current request aimed to implement that designation through appropriate zoning.

Wuertz Family History and Farming Challenges

Greg Wuertz provided personal context for the proposal, explaining that his family has deep roots in Pinal County. His grandfather and grandmother, Fred and Eunice Wuertz, moved from South Dakota to Arizona in October 1929 just before the Depression started, seeking relief from blizzards. The family has been farming in the region ever since.

Wuertz described how water scarcity has affected agriculture in the region, citing his father’s prediction that “if you farm long enough here in Pinal County, you’re gonna see what I saw in the ’50s and ’60s, and that’s seeing farmland go back to desert.”

The Wuertz family viewed the project as part of their retirement strategy. None of their four children plan to continue farming, and Greg and his wife Loralee are “the last to do farming in my side of the family.”

Loralee Wuertz added that her husband can’t farm the land they own because “we don’t have the water, nor will we ever get any more water, because it’s always gonna go to municipalities.”

Kirk McCarville, who worked with the family on the project, highlighted the water challenges: In the San Carlos district, there’s 50,000 acres of irrigated farmland, but with current water allocation, only 8,500 acres can be farmed. Greg Wuertz can only farm 27 of his 160 acres due to water limitations.

Energy Needs and Grid Stability

Linda Brady, representing Salt River Project (SRP), spoke in support of the project, noting that SRP plans to purchase power from the NextEra battery storage project. She addressed a common misconception, stating “All the power we generate and purchase is for our local customers here.” She clarified that while SRP sells excess power on the wholesale market, “we don’t profit off that, we reinvest it back into the grid to make it even better and to keep costs lower for our customers.”

Brady emphasized the importance of battery storage: “They can store power when energy demand is low, and then we can release it when it’s high. And that’s very cost-effective, and again, keeping costs low for our customers.”

Scott Riggins presented concerns about renewable energy reliability, citing recent events in Spain where a solar-powered electrical grid shut down. He read from The Wall Street Journal: “Life changed for Spaniards at noon on Monday when the sun at its peak, the country’s largely solar-powered electrical grid shut down.” Riggins used this example to draw parallels to the potential risks he saw in Pinal County’s increasing reliance on solar energy. He also cited The New York Times, which reported that Spain had proudly announced sufficient renewable power generation just two weeks before experiencing an 18-hour blackout. According to Riggins, analyst Pratikee Ramdas warned that “when you have more renewables on the grid, then your grid is more sensitive for these kinds of disturbances,” suggesting that Pinal County could face similar vulnerabilities if it continued expanding solar projects without adequate backup systems.

Safety Considerations

Joseph Troncoso, Assistant Chief with Regional Fire and Rescue, addressed safety concerns about battery storage systems. He noted his department had studied lithium battery storage and conducted site tours of established facilities. “We’re confident that… They have a good plan, and that the practices that they’ve established reflect the best practices available in the industry and can do it safely.”

Brenda Hiscox from Coolidge raised safety concerns about battery fires. She stated that “multiple toxins are released into our lives, on every level” from solar facility fires and that despite claims of safety, these installations pose risks to surrounding communities. Hiscox claimed that when NextEra representatives were asked about fire procedures at a previous meeting, they stated “We let them burn, and we tell everybody to get away.” Hiscox referenced real-world examples including fires at the Monterey Bay facility in California, where she mentioned researchers found heavy metals in soil and water samples. She argued that despite increased utility solar development in the area, electric bills had risen significantly rather than fallen, with some Florence residents reporting 150% increases that forced them to choose between groceries, medication, or paying their electric bills.

Community Impact and Support

NextEra representatives highlighted their community involvement. Pew noted they had “provided a firetruck to the South Florence Fire District” and worked with the Coolidge school district.

Bonnie Palmer, a Coolidge resident since 1969 and member of the Coolidge Rotary Club, offered support for NextEra as a community partner. She described how NextEra had supported Rotary projects including the Dolly Parton Imagination Library, Hope Women’s Center, scholarships, youth leadership programs, and homeless projects. She added that NextEra had given “hundreds of thousands of dollars to the schools, to the libraries,” without seeking recognition.

Coolidge Officials’ Opposition

City of Coolidge representatives strongly opposed the project. Phil Garthright, Senior Planner for Coolidge, explained that the project didn’t conform to the city’s November 2024 general plan approved by voters. He clarified that while NextEra characterized the area as not slated for near-term development, projects were already happening in similar directions from the city center.

Tom Bagnall, a Coolidge Councilmember, described his negative experiences with NextEra properties near his home, including fires at an inverter and under solar panels. He characterized the company as “locusts” and stated “we’re done with it in Coolidge. We don’t want any more.”

Tom Scott, Vice Chairman of Planning and Zoning for Coolidge, noted that approximately 40,000 acres (62 square miles) of Pinal County have already been approved for solar development. He challenged claims about job creation, stating that while construction creates temporary positions, “after they’re built, there’s no jobs. There’s no full-time jobs. There won’t be a full-time job at this location. There’s nothing there,” suggesting the project would not offer long-term employment opportunities.

North-South Corridor and Development Plans

The proposed North-South Corridor highway became a point of contention during discussions. Pew argued the project wouldn’t obstruct the corridor, stating “we’re not in the way of the freeway, because the freeway location hasn’t been determined yet.” He added that NextEra had been “involved in those studies” and had provided their plans to ADOT.

However, Garthright countered that the project conflicts with the city’s plans for the area, noting that Coolidge had opposed the land use change at a county meeting in 2024.

Economic Impact and Taxes

NextEra and supporting experts highlighted potential tax benefits. Luis Cordova from Rounds Consulting Group stated that the project “has the potential to generate millions of dollars to support essential services, like roads, public safety, and more. In fact, the revenue could be used to lower the property tax for residents.”

Pew claimed that one year of tax revenue from the solar project would equal what the county would collect from the agricultural land over 30 years.

Conclusion

Following the failed vote on the rezoning request, the related Planned Area Development overlay proposal died for lack of a motion, as the rezoning request had already failed. The rejection marked a setback for NextEra Energy Resources and the Wuertz family, who had been working on the project since 2022.

The debate highlighted ongoing tensions in Pinal County between renewable energy development, agricultural traditions, community growth plans, and property rights as the region continues to face decisions about future development and competing land uses.