Commission Seeks Answers to Numerous Questions About Proposed Solar Facility

The Planning and Zoning Commission has postponed a decision on the proposed Selma Energy Center solar project after a lengthy discussion raised numerous unanswered questions about the development. The commission voted unanimously during its April 17 meeting to continue the public hearing until May 15, giving the project developers time to address commissioners’ concerns.

Project Overview

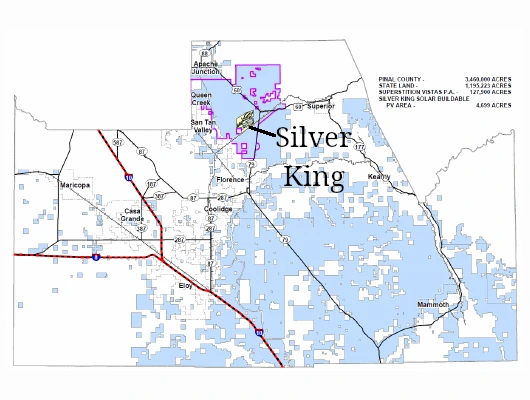

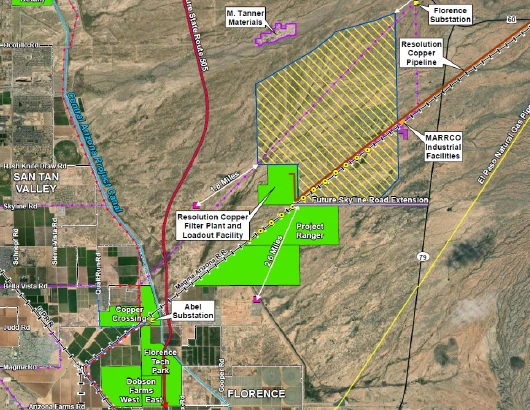

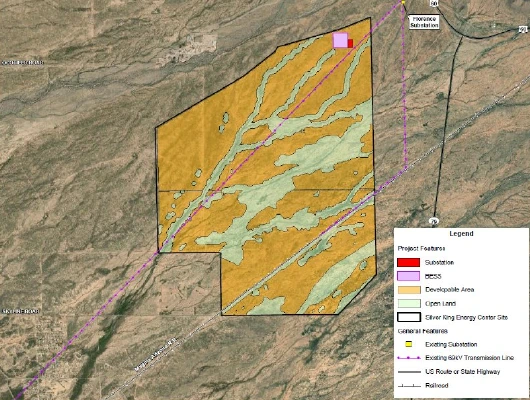

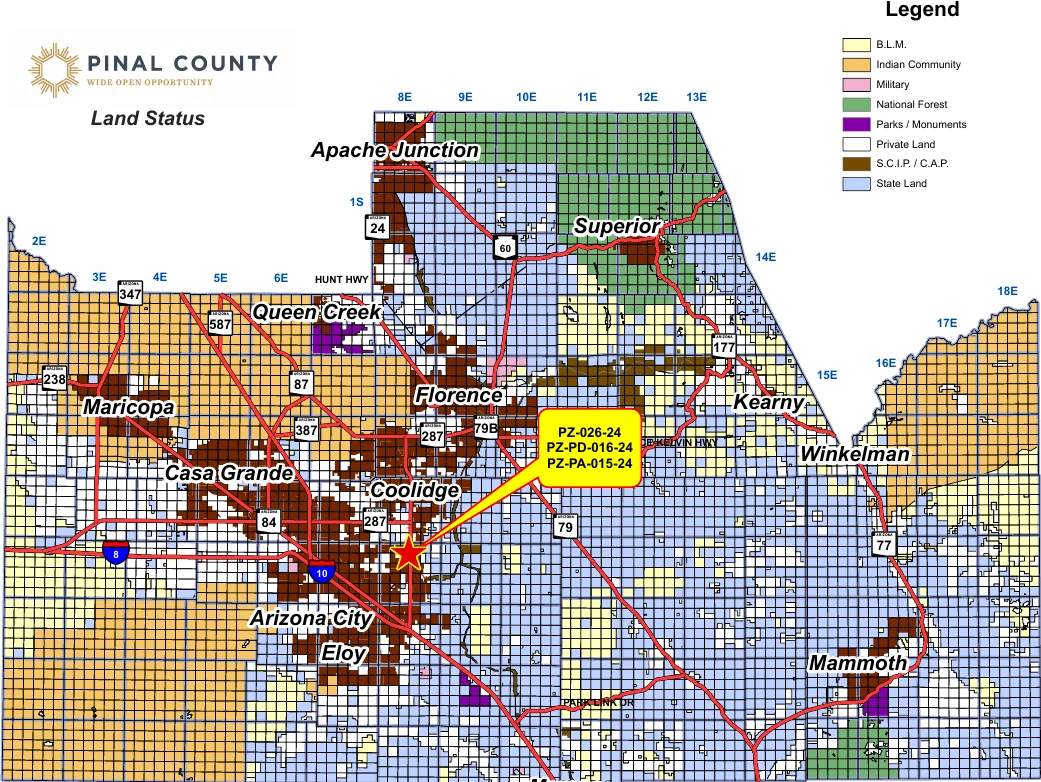

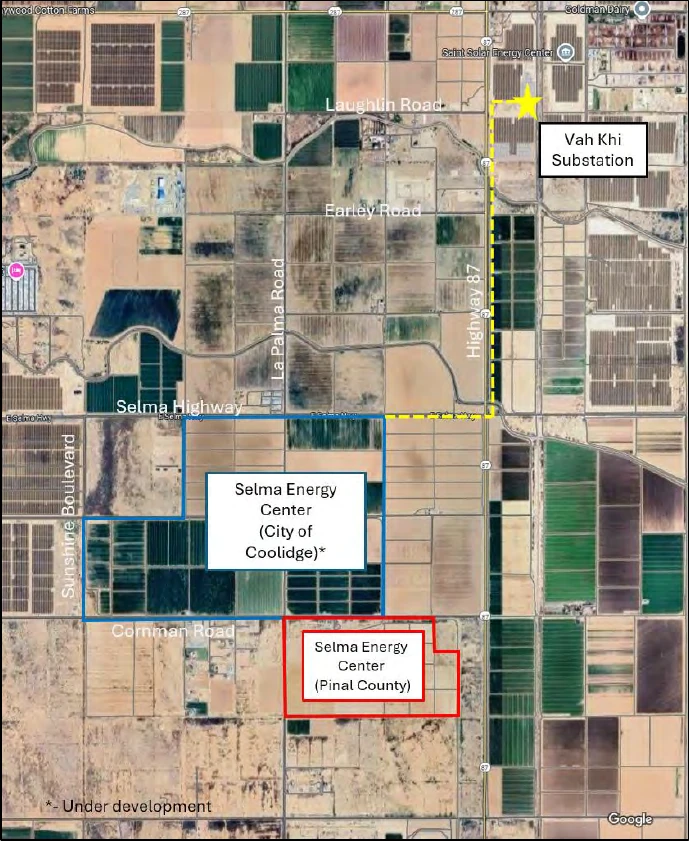

NextEra Energy Resources, through agent Ralph Pew of Pew & Lake, PLC, seeks approval for three related cases concerning a 260-acre photovoltaic solar generation facility. The property, owned by the Sharon Buell Family Revocable Living Trust, sits at the southeast corner of South La Palma Road and East Cornman Road in unincorporated Pinal County between the City of Coolidge and the City of Eloy.

The three applications include:

- A non-major comprehensive plan amendment to change the land use designation from Employment to Green Energy Production

- Rezoning from General Rural (GR) to Industrial (I-3) zoning

- A Planned Area Development (PAD) overlay to modify development standards

The 260-acre project would be part of the larger 1,052-acre Selma Energy Center, with 792 acres already approved in the City of Coolidge through conditional use permits issued in 2018. According to NextEra representatives, the facility would provide 150 megawatts of solar energy, meeting approximately 30% of Salt River Project’s 500-megawatt need identified in a 2023 request for proposals.

Jurisdiction and “County Island” Concerns

Vice-Chairman Robert Klob raised concerns about approving development in a “county island” – unincorporated county land surrounded by municipal boundaries. He recalled problems from the Phoenix metro area where such islands created jurisdictional confusion.

“These county islands that have occurred… I’m gonna go back into my Chandler days… that just left all these little marks,” Klob said. “It just created havoc for those cities as they were being annexed later on… It was, the county didn’t want to address it. The city said, ‘It’s not ours.'”

Klob questioned why the developers hadn’t sought annexation into Coolidge since the project would connect to the already-approved portion in that city. Pew responded that annexation conversations hadn’t occurred, noting that “in annexations, that’s a conversation between property owner and the municipality.”

Solar Policies and Opposition from Nearby Cities

The City of Eloy submitted a letter of opposition to the project, citing several concerns:

- The city’s ordinance (23-950) prohibits utility-scale solar facilities north of I-10

- The land is designated for estate residential in Eloy’s future planning

- Concerns about fire service coverage

- Inadequate development standards for buffering and landscaping

During the hearing, Phil Garthright, Senior Planner for Coolidge, orally expressed opposition on behalf of the City of Coolidge. While the city had approved the 792 acres of the project within its boundaries, Garthright stated they opposed the county portion from a “policy standpoint.” He explained that Coolidge’s general plan designates the area for business, commerce, and urban neighborhood uses.

“The notation of going to an I-3 here is technically, as far as we’re concerned, a noncompliant land use situation,” Garthright said, noting that Coolidge would not allow its highest industrial zoning (I-2) in areas designated for urban neighborhood or business commerce.

Project Details and Landscaping

The project would include solar panels, inverter stations, collection lines, perimeter fencing and gates, internal access driveways and roads, and water storage facilities for landscape and fire suppression needs. Kyle Whittier, a director from NextEra Energy Resources, emphasized that no battery energy storage system (BESS) would be included in the county portion of the project.

Commissioner Scott raised questions about the height of the solar panels relative to the proposed seven-foot chain link fence, noting that when pivoted to track the sun, the panels would extend several feet above the fence line.

The developers indicated the entire perimeter of the project would include landscape buffering outside the fence, which Planning Supervisor Sangeeta Deokar confirmed meets the county’s landscape requirements. Chairman Mennenga expressed concerns about landscape maintenance, stating that existing solar farm landscaping looks horrible and that developers “put ’em in, and you’re, like, gone.”

Power Distribution and Local Benefits

Commissioner Karen Mooney questioned whether the power generated would benefit the local community. Pew acknowledged that while the project would contract with Salt River Project (SRP), the energy wouldn’t necessarily stay in Coolidge or the surrounding area.

“We can’t track who SRP sells power to,” Pew explained, comparing it to cotton production: “This is the cotton kingdom of the world, right? Not every square inch of cotton stays here… It’s needed in other places.”

Commissioner Tom Scott pointed out that SRP doesn’t currently provide electricity in Coolidge, questioning the local benefit of the facility.

Location Strategy and Environmental Concerns

Scott questioned why utility-scale solar facilities are placed near populated areas rather than in more remote locations along transmission lines. “Why do you want to position these things where people live where it affects their quality of life?” he asked.

Kyle Whittier explained that the location was chosen based on SRP’s system studies identifying where resources are needed to service load, and proximity to the existing Vah Khi Substation approximately two miles away.

“Putting it out far out does not do as well servicing that load,” Whittier said. “The ability to interconnect just anywhere along a transmission line isn’t quite as simple as that.”

Scott raised concerns about dust control on the property, noting the area’s soil type (La Palma silt loam) becomes extremely fine when disturbed, creating visibility hazards during high winds. He described past traffic accidents in the area due to blowing dust when farmland was between crops.

Scott also questioned how the company would manage vegetation growth after removing existing plants, referencing a fire at NextEra’s Storey facility that he attributed to unmanaged vegetation. Whittier acknowledged the company has landscape management methods but couldn’t provide specifics.

Economic Impact and Tax Revenue

Pew cited studies indicating solar projects generate tax revenue through three primary sources: personal property tax, transaction privilege tax, and property tax. He estimated that a 200-megawatt, 1,200-acre solar project would generate about $27.3 million over its lifetime for the county, special districts, and school districts.

Decommissioning Concerns

Multiple commissioners expressed concerns about decommissioning plans when the project reaches the end of its 25-30 year lifespan.

“If you’re going to tell us that you’re gonna put the land back, how is that gonna happen? You can tell us how it’s gonna go up, how’s it gonna come down?” asked Commissioner Mooney.

Scott questioned whether financial responsibility for decommissioning would rest with the limited liability company (LLC) created for the project or with NextEra itself. He worried that the LLC might declare bankruptcy to avoid decommissioning costs.

“My fear is, is when we get to be three or four months away from the decommissioning… for the last 25 years, all the revenue has flowed through this LLC up to NextEra. There could be a possibility in a business strategy that you just remove yourself from this liability,” Scott said.

Whittier insisted this wasn’t NextEra’s practice but couldn’t provide specific details about decommissioning costs or procedures. “NextEra is committed to being a long-term owner, operator, neighbor, and that is not something that we would do,” he said.

Continuation Decision

Chairman Mennenga expressed frustration with the lack of concrete answers from the applicants. “We’ve been asking the same questions for three or four years here now on these solar companies and we still get the same answer, ‘Well, that’s a great question. I’ll get back to you,'” Mennenga said.

The commission voted unanimously to continue all three cases to the May 15 meeting, keeping the public hearing open. Applicants will be expected to return with detailed answers to the many questions raised during the April meeting.

Next Steps for the Project

The future of the Selma Energy Center project now depends on how thoroughly NextEra and its representatives can address the commission’s concerns at the May 15 meeting. If the Planning and Zoning Commission recommends approval, the proposals would be forwarded to the Pinal County Board of Supervisors for consideration.

When asked if the 792-acre portion in Coolidge would proceed without the county portion, Kyle Whittier responded: “The goal, of course, is to move forward with all of it, but our goal is to provide the power to SRP that they’ve needed.” If approved, the completed 1,052-acre facility would help meet SRP’s growing energy needs in response to population growth and increased industrial development in the region.