Key Points

- The Pinal County Planning and Zoning Commission voted 6-2 on October 16 to recommend approval of the Griffin Energy Project’s comprehensive plan amendment.

- The 2,685-acre facility, proposed by Copia Power, combines solar panels, battery storage, and natural gas generation to supply power directly to a planned data center.

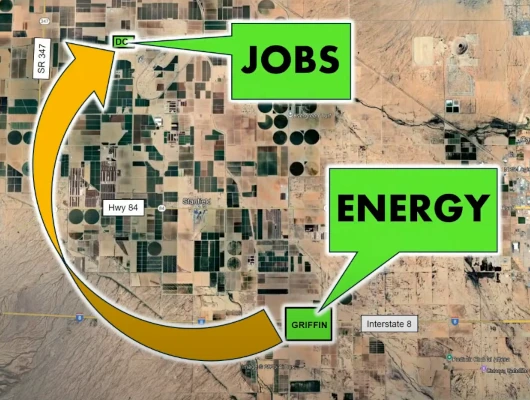

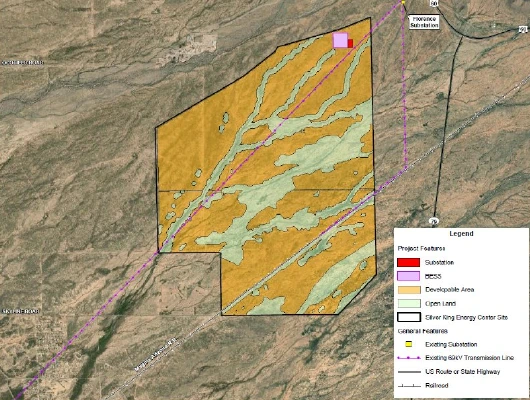

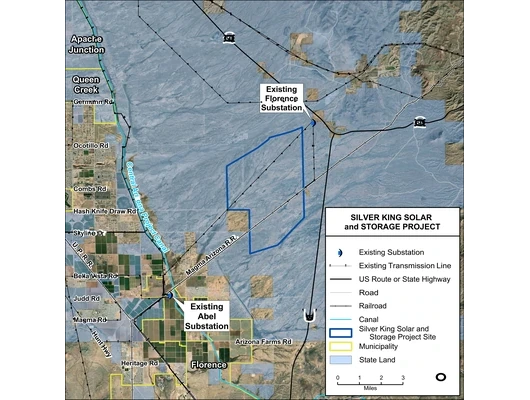

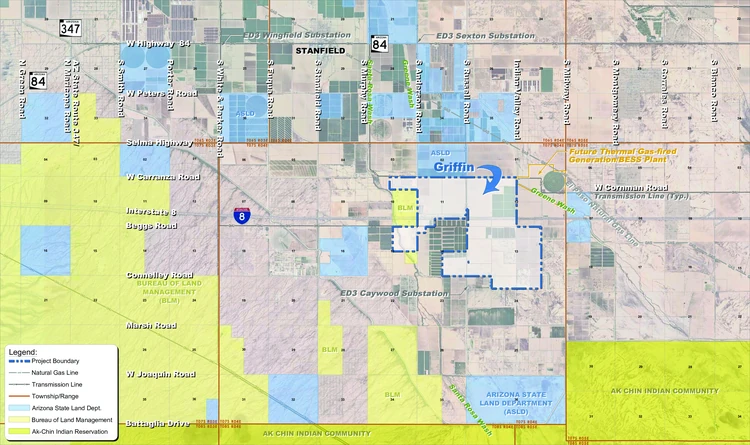

- The project site is located southeast of Stanfield, Arizona, and extends on both sides of Interstate 8 between the Santa Rosa Wash and Greene Wash.

- The project now moves to the Board of Supervisors for final consideration before rezoning or construction can begin.

- Commissioners Tom Scott and Karen Mooney opposed the project, citing concerns about farmland loss, project scale, and temperature effects.

- Developer representatives emphasized the project’s economic benefits, projecting $10 billion in investment, over $1.1 billion in tax revenue, and more than 1,000 jobs when paired with the data center.

- Supporters argued the project helps repurpose farmland affected by the loss of CAP water, while critics raised concerns about open space, wildlife corridors, and dust control.

- The project’s hybrid energy mix aims to provide price stability and attract large-scale industrial users seeking clean and reliable power.

Commissioners recommend approval of 2,685-acre energy complex to power future data center

The Griffin Energy Project, a 2,685-acre integrated solar, battery, and natural gas facility proposed by Copia Power, advanced another step forward. The Pinal County Planning and Zoning Commission voted 6-2 on October 16 to recommend approval of its comprehensive plan amendment. The large-scale energy development sits between the Santa Rosa Wash and Greene Wash and is designed to power a data center project—located south of the Ak-Chin Indian Community east of the City of Maricopa—that commissioners reviewed in the following agenda item that same day.

Court Rich of Rose Law Group, representing developer Copia Power, said the solar and battery components would each provide “up to 550 megawatts” of capacity, while the gas-fired power plant would generate “up to 500 megawatts.”

This recommendation follows up on our previous coverage, where commissioners initially expressed concerns about extensive flooding risks across the site. The project now moves to the Board of Supervisors for final consideration on the comprehensive plan amendment before any rezoning or construction can begin.

Direct Connection to Data Center Creates Different Dynamic

Rich emphasized what distinguishes this solar project from others the commission has reviewed.

“This is a solar project, but it’s not just a solar project and it’s different than every single other solar project you’ve ever seen,” Rich told commissioners. “It is directly designed to feed a project, the next project that’s coming before you, this data center that’s going to be in the county.”

Rich was referring to the Energy Generation and Technology Campus. The campus is planned east of the City of Maricopa and south of the Ak-Chin Indian Community. Commissioners would review that project later that same day.

Rich presented economic analysis from Elliott Pollack & Company projecting the combined projects’ impact. The projects would generate almost $10 billion in total investment. Tax revenue to the state and county would exceed $1.1 billion over 25 years. They would create 508 direct jobs plus 588 indirect jobs yielding $66 million in wages annually.

The pairing of generation with consumption addresses a recurring question Vice Chairman Robert Klob raised about power distribution.

“We’ve heard so many times that once it goes into the pipeline, it’s for everyone to use,” Klob said. “Yet we’re hearing today of two cases now where it’s somewhat dedicated to theirs.”

Earlier in the day, commissioners heard the La Osa Energy and Data Center project, which also proposed generating its own power rather than relying solely on grid infrastructure.

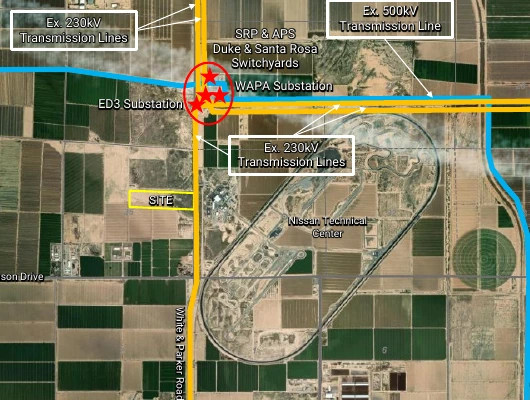

Brian Yerges, representing Electrical District Number Three, explained the practical reality behind these arrangements.

“Nobody’s going to build a solar project and just sell it into the grid without any commitments to buy that,” Yerges said. “That’s not the way the industry works. There has to be an off-taker.”

Yerges noted ED3 has worked with the applicant for months on interconnection studies.

“When we started looking at the interconnection process, we required a down payment of several hundred thousand dollars to do that study work,” Yerges said. “This ensures that if the project falls through, regular ratepayers haven’t paid for studies on a development that never materialized.”

Scott Questions Solar Tax Claims; Rich Points to Data Center Revenue

The economic discussion took a detailed turn when Commissioner Tom Scott pressed on property tax benefits. He drew from his experience with solar facilities around Coolidge.

“The property tax is important, but the property tax isn’t substantial like we’re led to believe,” Scott said. “The problem is it goes to the state, and the state doesn’t bring it back to the point of origin. It just kind of sprinkles it around the state.”

Rich clarified the tax projections he presented apply to the data center equipment, not the solar facility.

“The tax benefit numbers I was quoting are from the data center project that is enabled by all this,” Rich explained. “That is class 1 property, is the way it’s taxed. And so that’s locally assessed, locally collected, just like any other property tax in the state.”

The local assessment and collection Rich described for data centers contrasts with solar facilities. Scott indicated solar facilities send tax revenue to the state for redistribution rather than directly benefiting the county where they’re located.

Under Arizona Revised Statute 42-14155, renewable energy equipment including solar facilities is valued at 20% of depreciated cost through 2040. Depreciation is capped at 90% of original cost. Class 1 commercial and industrial property, according to ARS 42-12001, is valued at full cash value.

Scott referenced conversations with the county assessor about solar depreciation schedules. Earlier in the day during the La Osa hearing, Scott explained how Arizona statute allows 10-year depreciation on solar facilities. Tax revenue drops significantly after the first decade of a 25-year project.

“After you take all your deductions, batteries are not taxable, incentives from the government deducted out, it’s roughly 50% plus or minus,” Scott said in that morning session. “After 10 years, the value goes back to the net value of the land, whether it be farmland or vacant land, plus around a 10% bump because the infrastructure is still there.”

Rich confirmed the substantial tax benefits he presented would come from the data centers, not from the Griffin Energy solar facility. The data centers are part of the separate Energy Generation and Technology Campus project commissioners reviewed in the following agenda item.

Landowner Testimony: CAP Water Loss Forces Difficult Choices

Dan Thelander, a partner in Stanfield 1295 LLC and one of the property owners, provided testimony supporting the project. His family leases and manages 3,400 acres in the area, including the 2,685 acres proposed for solar development.

“We farm almost all of this land,” Thelander told commissioners. Out of 3,400 acres they lease, Thelander said they’re “only farming 1,400, which is about 40% of the land” because they’re “only living on the pump water now.”

The Maricopa Stanfield Irrigation District lost its CAP water allocation, eliminating 2,000 acres of productive farmland from Thelander’s operation.

“We’re already losing most of the farmland because of lack of water,” Thelander said. “That farmland now is either weeds and then we have to get out there and disc it down and then it’s another PM10 issue.”

Commissioner Bryan Hartman asked Thelander to explain PM10 for commissioners who might be unfamiliar with the term.

“So we have to keep the weeds down and we go out there and disc it down. It gets to be light, fluffy soil. The wind comes up and you’ve got a dust storm,” Thelander explained. “When we’ve got crops on it and it’s windy and it blows, it’s no big deal. So having vacant farmland is more of an issue for dust than if you had it covered up with solar panels.”

He explained converting the land to solar would allow the irrigation district to redirect well water. The water could flow north through the East Main Canal or south to other farmland with even less water access.

“The 1,400 acres that we are losing because it’s going to solar, there will be 1,400 more acres grown to the north or the south because that water’s going to go other places,” Thelander said. “So the net result is going to be the same amount of agriculture.”

Thelander emphasized the property continues generating property tax bills despite producing no income.

“We still pay property taxes on all this land, but there is nothing that we can do to earn any productive income off of it because it’s all row crop farms and we don’t have the water,” he said.

Trail Corridor and Open Space Stipulations

Desert ecologist Cyndi Ruehl worked extensively on the county’s Open Space and Trails Master Plan. She raised concerns about the project’s impact on designated corridors.

“What we have here is a project that is proposing to take designated open space,” Ruehl told commissioners, referencing the Santa Rosa and Greene Washes. “These weren’t just randomly chosen. They came from scientific rigor and public rigor, and also aligned to our comp plan policies and goals.”

Ruehl emphasized the importance of maintaining connectivity.

“These are corridors. Everything moves through corridors, not just animals. It’s the heartland, it’s the artery of an ecosystem,” she said. “To cut off a corridor is to make it functionally useless, not only there, but on both ends of the ecosystem, all the way down into Pima County, up into Maricopa County.”

She noted a proposed multi-use trail runs through the project area, part of a trail system connecting Pima County to Maricopa County.

“No hiker is going to be walking through the middle of a solar field, nor a wild animal, no horse, equestrian person,” Ruehl said.

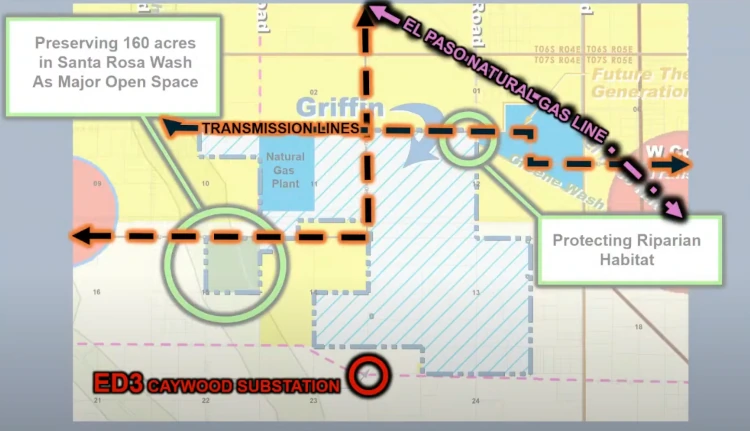

Rich responded that the project sets aside 160 acres, which he said is larger than the corridor on the west side of the wash. The presentation indicated this preserves open space in the Santa Rosa Wash and protects identified riparian habitat in the northeast corner near Greene Wash. Rich said the trail along Interstate 8 would be accommodated.

“The trail on the map is right along I-8, and we are on both sides, and so we will set aside that land,” Rich said.

Klob noted specific trail stipulations and allocations would be addressed during the rezoning phase rather than the comprehensive plan amendment stage.

Robin Davis, a Hidden Valley resident, expressed support for Ruehl’s concerns. She emphasized that stipulations protecting corridors and trails must be required before the project advances. While Davis said she doesn’t oppose solar itself, she told commissioners: “What I’m getting out of all this today, and all the times I’ve spoken to you, is this all means that the tax revenue, the power needed for people’s AI and data storage is way more important than the people who live out there.”

Temperature Effects: Anecdotal Experience and University Research

The commission heard competing perspectives on whether solar facilities increase local temperatures.

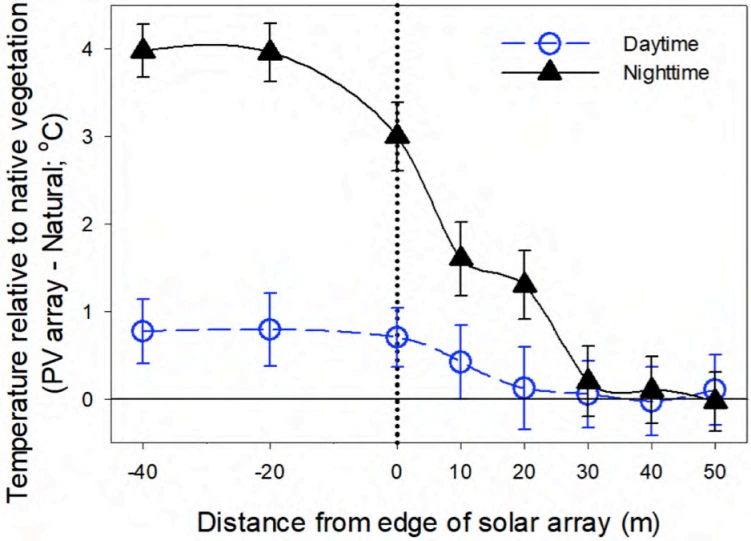

Rich cited University of Arizona research by Professor Greg Barron-Gafford showing no detectable temperature increase beyond 100 feet from solar arrays.

Commissioner Karen Mooney countered with residents’ direct experiences.

“I’ve talked to residents that actually live near these, have been there and seen their temperature gauges,” Mooney said. “I still take it from the residents that are actually living in those areas that are affected and they can see it on their outside temperatures.”

Commissioner Tom Scott raised additional concerns about measurement methodology.

“The solar does impact the temperature,” Scott said. “Where you need to check is like a year before you build the project and then compare it to what’s inside the project and that’s where the difference is.”

Scott cited research by Dr. Joshua White, a Coolidge native. White completed his doctorate in climatology at Arizona State University.

“Solar panels create artificial high pressure overhead due to the heat production from the panels themselves which creates a laminar flow over the panels,” Scott read from White’s research. “This flow makes dust flow over these panels easier. The general air flow over the panels will likely be the path of least resistance and funnel the wind towards them, which will also bring more dust.”

Scott described conversations with a pecan farmer surrounded by solar facilities on three sides. The farmer reported ambient temperatures seven to ten degrees higher prevented his trees from going dormant properly.

“When your trees don’t go dormant, they produce, but they don’t produce what they should,” Scott explained.

Professor Barron-Gafford, who drove from Tucson to address the commission, defended his research methodology. His 2016 study “The Photovoltaic Heat Island Effect” was published in Scientific Reports. The study found solar installations were 3-4°C warmer than nearby wildlands at night. However, the warming effect disappeared at distance.

“We are sticking digital thermometers, we measured them within the array, moving in a transect line of sensors as you moved out of the array,” Barron-Gafford explained. His team found no distinguishable temperature effect beyond 100 feet from the solar arrays.

He noted that, as of this meeting, White’s work had not been published or peer-reviewed, making it difficult for other scientists to critique or validate.

“I’m familiar with Josh’s work. It has not been able to be critiqued or reviewed by other scientists, which is kind of the basis for how we do scientific advancements through time,” Barron-Gafford said.

Regarding the before-and-after measurement concern Scott raised, Barron-Gafford explained his team’s approach. They used satellite thermal imaging to compare temperatures before and after installation.

“Since I can’t time travel, what we did was use the satellites that are overhead taking pictures of us constantly and they have thermal pictures of these lands,” he said. “We measured the temperature that that satellite is monitoring before and after installation and found no effect.”

Agrivoltaics and Vegetation Management

Rich’s presentation included photographs of native vegetation growing beneath solar panels at a Copia facility in the Harquahala Valley. The photographs emphasized the developer’s commitment to avoid chemical herbicides.

“Copia does not do that,” Rich said regarding chemical spraying. “They used the native seed, they let it grow. If there are weeds, they mechanically pull them.”

Scott countered that agrivoltaics—growing crops beneath solar panels—remains largely theoretical in Pinal County despite success in states like Colorado.

“We don’t see any of it here,” Scott said. “I think the gentleman from the U of A, I had a talk with him in the parking lot after a meeting, it’s been a few years ago, talked about how they did a study somewhere around the biosphere. But we just don’t see that in any of the sites that are currently in existence in this county.”

Barron-Gafford confirmed his team actively researches agrivoltaics at the Eastline site on Selma Road. They are planting beans, corn, and squash, with plans to add prickly pear and agave.

“The fact that we can grow plants two feet from the solar panels and see them do better tells me that there’s no way that you’re going to be negatively impacted a mile away, half mile away, anything more than a hundred feet away,” Barron-Gafford said.

Vegetation Management and Fire Risk: Learning from NextEra

Scott raised concerns about vegetation management beneath panels, referencing an October 2024 fire at NextEra’s Story facility.

“NextEra, the way they take care of the weeds is they just allow them to grow, kind of like what you’re doing, and they cut them twice a year,” Scott said. “So there’s growth on the ground. And one way or another, something hit a reflection and caused a fire out there. And the only way that was able to burn in the panels was because they had matter on the ground there.”

Scott noted the vegetation in Rich’s photographs appeared sparse and spread out, similar to alfalfa, but expressed concern about fire risk with accumulating dry matter.

Rich committed to addressing vegetation management in detail during the rezoning phase. He stated Copia would stipulate to mechanical removal rather than chemical treatment.

Fire Safety: New Technology and Heat Suppression

Arizona City Fire Chief Jeffrey Heaton spoke in support, describing advanced fire suppression technology that the district plans to deploy.

“We have the new technologies, these LFP batteries, the new panels. They’re resistant to breakage, they’re resistant to runaway thermal reactions,” Heaton explained. “We’ve partnered strategically with not only this project, but other projects, to come up with new technologies that use substantially less or no water.”

Heaton described surfactants that suppress heat rather than extinguish fire.

“The surfactant bonds 50 times greater than foam does, so it uses less water,” Heaton said. “What it does is it interrupts the fire tetrahedron to break both the chemical reaction and smother the oxygen out of the fire. It absorbs that thermal reaction of those batteries.”

He distinguished surfactants from older foam technology found to contain cancer-causing agents.

“We claim never to be a foam. A surfactant is a completely different technology,” Heaton clarified. “We’re not going to pour water on these batteries. We’re going to use those surfactants that use about 10% or less of water.”

Scott asked about heat suppression versus fire extinguishment. Heaton confirmed the surfactant surrounds the operation to suppress heat transfer to adjacent battery units. It does not inject material into burning batteries.

“Heat suppression is all that is,” Heaton said, contrasting with water application that merely cools adjacent equipment.

The chief emphasized the new district would bring fire and emergency medical services to an area currently lacking coverage. The services would be funded through developer commitments.

Energy Mix Provides Price Stability

Rich addressed why the project combines solar with natural gas generation despite gas plants producing more power per acre.

“A lot of the entities that want to locate in data centers require a certain amount of clean energy,” Rich explained. “These customers often say, ‘I need it to be all clean, or 50% clean,’ or whatever it is… Being able to offer clean energy as an option will help attract businesses to locate in the data center.”

He emphasized solar provides cost predictability.

“The price of the sun never goes up or down,” Rich said. “If there’s a storm in Texas, our gas prices go way up. The sun just costs what it costs. Once you build the solar facility, the sun is free and you never have to pay for that energy.”

Commissioner Gary Pranzo questioned the emerging trend of industrial developments generating their own power rather than relying on utility infrastructure.

“I’m starting to see a different model for industrial development being put forward where if you want to do something industrial, you need to bring your own power,” Pranzo said. “I’m a little bit worried about it can trickle down to residential or small commercial and it takes up land, there’s no question about that.”

Rich explained the approach reflects current power constraints.

“There’s constraints on power right now. Everybody that wants to build a factory or a data center can’t just go do it, because for the first time ever in Arizona, utilities just don’t have enough power for everybody,” Rich said. “If the person who needs the power can bring the infrastructure to get it to them, to generate it and bring it to them, that is a really efficient way of doing it.”

He argued this approach benefits other rate payers.

“Instead of asking rate payers to go out and socialize the cost of new electricity and then just pay for it, pay it back over time by buying power, they’re actually investing the capital upfront to build it all,” Rich said.

Yerges confirmed ED3 supports this model for managing risk with large loads.

“When you’re talking about a data center that is several hundred megawatts, that introduces a lot of risk to other rate payers,” Yerges said. “It wouldn’t be appropriate for ED3 to take on all the risk and put that on the backs of residential rate payers or our ag customers.”

Commissioner Votes and Rationale

Commissioner Karen Mooney explained her no vote, citing the project’s scale.

“This is one of the large ones. 2,685.58 acres,” Mooney said. “It’s too large a project for me.”

She noted the Citizens Advisory Committee recommended approval 11-2, though some members had departed by the time of the vote.

Commissioner Tom Scott cast the second no vote, expressing concerns about converting productive farmland despite acknowledging water challenges.

“Probably 90% of this project’s on active farmland and that’s a pretty hard trade-off for me,” Scott said.

Commissioners Bryan Hartman, Wallace Keller, Albert Lizarraga, Daren Schnepf, Gary Pranzo, and Vice Chairman Robert Klob voted to recommend approval, with the 6-2 vote sending the project forward to the Board of Supervisors.

The Board of Supervisors will consider the comprehensive plan amendment at a future meeting. If approved, Copia Power would then pursue rezoning from General Rural to Planned Area Development with Industrial zoning. At that stage, detailed stipulations regarding trails, vegetation management, fire protection, and other operational aspects would be addressed.